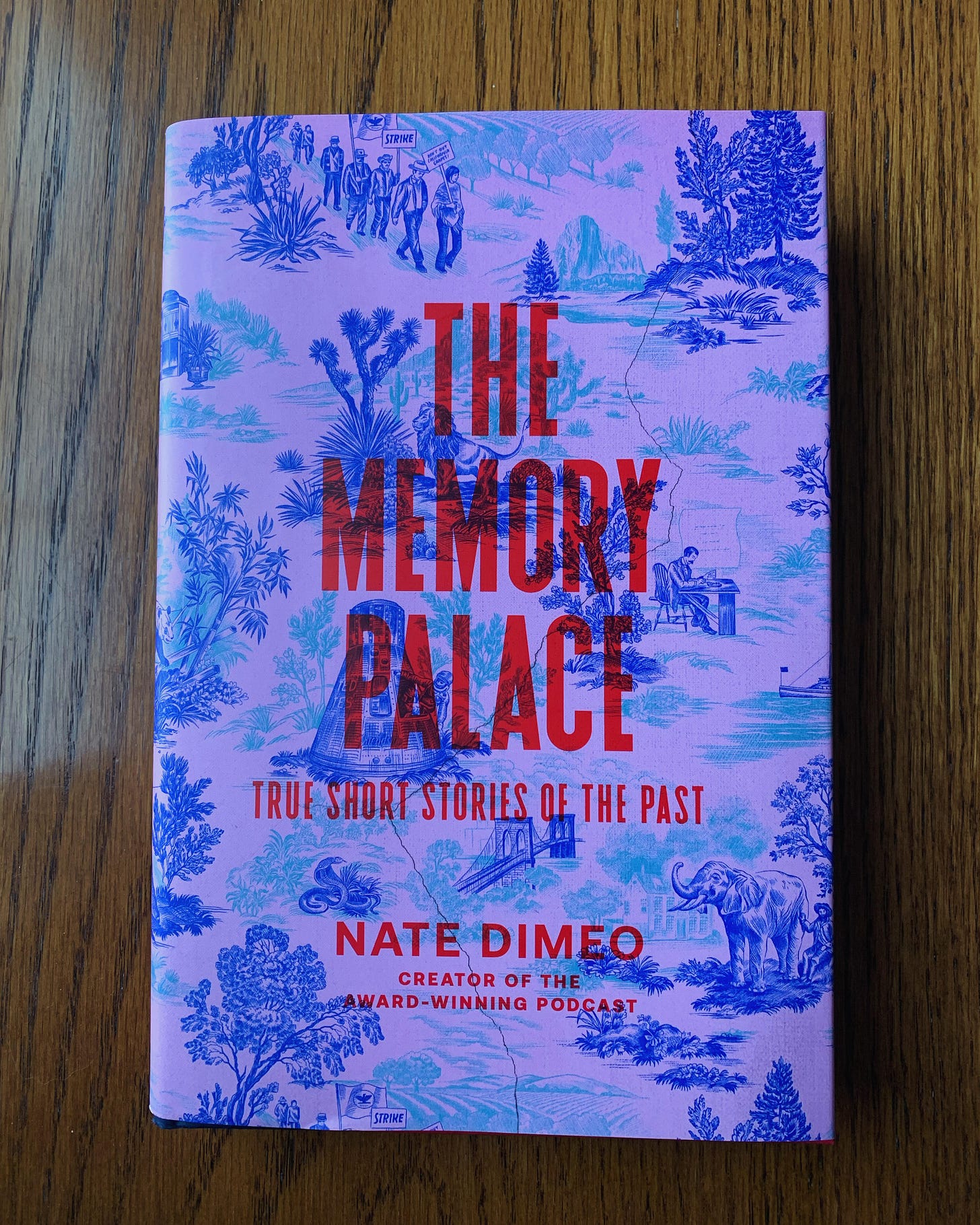

One of my original ideas for the organizing principle of this substack was the memento mori—objects/ readings/ reflections that remind us of the fleeting nature of life and the inevitability of death. Ultimately, the prospect of writing at least 52 posts about death felt a bit grim (and while I am not particularly superstitious it felt a bit like it would be inviting unwanted attention from a Grim Specter whose gaze I would just as soon avoid). But as I was finishing up Nate DiMeo’s new book The Memory Palace I was struck by the following passage,1 where he sums up the idea behind his podcast, and his fascination with history:

“I made a practice of going to every museum, every historic home and marker within driving distance, both because I loved them and because I felt my life slipping by every day, even at twenty-three. I found that engaging actively with history—with stories of the past, of lives with beginnings and middles and ends, with periods of strife that felt unending but weren't, or peace or joy that couldn't hold—kept present the most valuable thing I knew: the fact that we are all going to die. And living in awareness of that made me live better. More bravely. Made me more attentive. More considerate. It was the simplest, most eternal of lessons (I knew that, even then), but I had noticed it was one you needed to relearn over and over. To this day, I write these stories in part because doing so well requires that I remember it.”

Nate DiMeo, The Memory Palace, page 287

What DiMeo captures here is an essential aspect of his work with the Memory Palace (both this book and the podcast2 that gave rise to it—both are excellent and well worth your time): the ability to make moments from the past feel alive and present and real. They remind us that the people who lived 100, 200, 800 years ago were just as real as we are, with the same sorts of hopes, fears, desires, and needs (which is an obvious idea, but one that often feels not 100% true when we (I) think casually about the past).3 DiMeo’s stories help remind us that all of these people—and by extension, all of their neighbors, and all of the other people who ever lived that we don’t hear stories about, almost all of whom are entirely forgotten now—were once just as alive as our own spouses, and the people we see each morning on the way to work, and at school drop off, and at Target—all of us, so alive to ourselves, so vital and important and, ultimately, transient.

I think DiMeo is right that holding the reality of our own inevitable death at the forefront of our minds is a. helpful in all sorts of concrete ways, and b. incredibly difficult to do. In general, we don’t want to think about the fact that one day we will cease to exist, and not too long after that we will be entirely forgotten. And our consumeristic and technophilic culture is, in many ways, constructed to obscure the existence of our own mortality, to distract us from thinking too deeply about, well, anything, but particularly about death. But it is right and good to do it; it helps us, I think, to be less afraid to live. When we remember that this is all going to end one day, we (hopefully) remember to spend the time we have more wisely.

I promise not every post here will revolve around a quote!, but as a scholar/ writer I do love a good block quote. There is something very satisfying about finding a passage that says exactly what you want it to say; but, somewhat ironically, as a reader I usually skim block quotes. I tend to find something jarring about the shift in tone or language between a long quote and the actual text that I’m there to read, and I figure the author will summarize or reflect on whatever they find meaningful about the passage they’ve quoted. I’d be interested in hearing how others feel about these kinds of long quotes when they are reading.

Quick aside about podcasts—I love them. I listen to them a lot. It started when I was a stay at home dad, caring for a pre-verbal child, and I would have NPR on in the background all the time as a form of adult company; later, even when I was working full-time, I usually worked from home, and it was somewhat comforting to have voices on in the background. I fell into the whole genre of podcasts where it’s just two friends talking about nonsense (I think of these as the Grantland—now Ringer—pods, which are usually about sports (I miss the Lowe Post!) or pop culture ephemera); a lot of times I haven’t even seen whatever it is the hosts are talking about, but the podcasts are still enjoyable (and sometimes even insightful) because of the hosts’ banter. But these podcasts don’t require one’s full attention; half the time when they’re over I couldn’t even tell you what they were talking about in any detail. But there are other types of podcasts where one really does need to listen closely and give one’s full attention, because what they are making is a form of art, meant to be savored. The Memory Palace definitely falls into this latter category.

Personally, this is one of the things that I love about my own field of literary scholarship. Not just diving into the plots of stories written in the past, and seeing how the themes of, say, Victorian Novels or Jazz Age stories still resonate with us today (though this is one of the great joys of teaching), but also the process of researching the lives of the people who created these stories. I love learning about writers from 100 or 200 years ago, or even back in Elizabethan England, and how their struggles with the actual process of writing mirror contemporary ones. And I find something very familiar and humanizing in exploring the messy worlds of influence and competition and inspiration that give rise to these stories that we are still reading so many years later.

1) love this podcast and that book design is gorgeous and someone really awesome must have gifted it to you

2) almost every time I listen to the memory palace, my brain snags in a groove about how Sherlock Holmes ALSO has a memory palace. But SH uses his memory palace to distance himself from other people, to categorize and re-sort facts and perceptions, in order to come up with some kind of solution only he can see. While Nate deMeo starts with a similar approach - building a space where memory and history have a home and can interact - but takes it further by 1) sharing it with others and 2) allowing the memories to bring him back into connection with the real world and others in a deeper way. I prefer Nate’s approach.

I used to listen to The Memory Palace quite often. I remember one story about an older gentleman that was moving out of a home he had lived in for an extraordinary amount of time. It was so tenderly written, but try as I may, I cannot find the episode.